Stand With Documenta

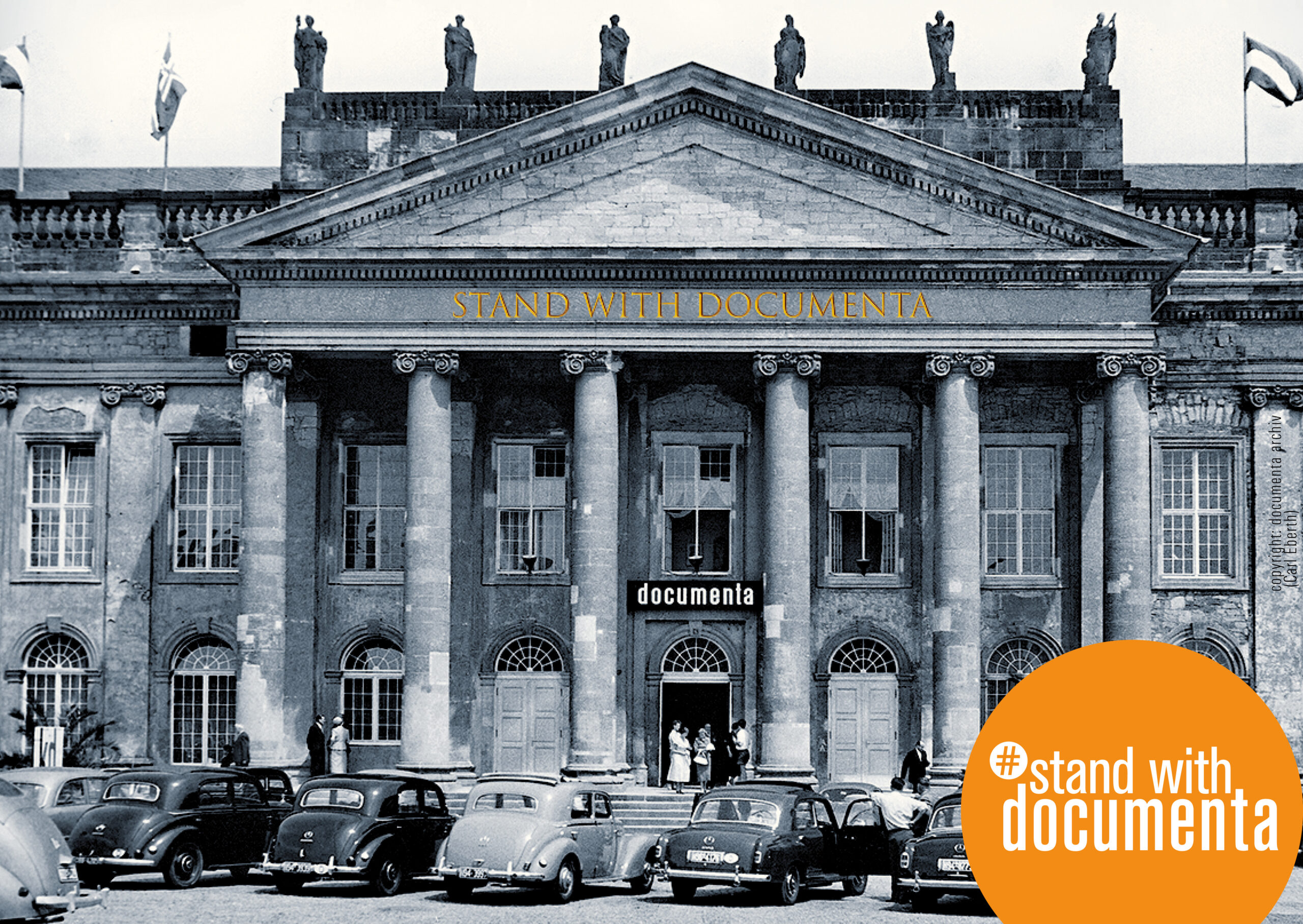

With the first and second documenta in 1955 and 1959, the initiator of the documenta Arnold Bode brought contemporary art from abroad, especially from the USA, back to Germany for the first time after the dictatorship of National Socialism. In doing so, he brought the other into your own. At the two exhibition venues – the Fridericianum and the Orangery in Karlsaue, which were still partly ruins at the time, the old and the new, our own and the others were mingled. The one became an enrichment of the other.

With this, the curator team around Arnold Bode and Werner Haftmann created an incomparable platform for an international dialogue beyond all borders, be it regional, national, ethical or gender-specific. The basis was created, among other things, by the German Constitution with its Paragraph on Freedom of Art and Science in what was then West Germany.

I was a Stranger, Obelisk at Koenigsplatz by Olu Oguibe, Documenta 14, 2017

I was a Stranger, Obelisk at Koenigsplatz by Olu Oguibe, Documenta 14, 2017

A large international audience also travelled with the international artists. With 134,000 visitors, documenta 2 recorded even more interested parties than its predecessor. (The steady increase in visitors continued from then on).

This was always made possible under the responsible, creative leadership of the curator team with support from the administration, which made the organizational implementation possible.

Man Walking to the Sky by Jonathan Borofsky, documenta 9, 1992

Man Walking to the Sky by Jonathan Borofsky, documenta 9, 1992

Of course, there have always been controversies, but in dialogues they resulted in the artists and guests who were invited and arrived not being perceived as degenerates or threats, but rather as enriching their own culture and vice versa. So both were always experienced as enriching the other.

One of the many examples in this sense is the creative intervention by Joseph Beuys under the title 7000 Oaks – Urban Forestation instead of City Administration for documenta 7 1982 under the artistic direction of Rudi Fuchs.

This was an artistic and ecological intervention that sustainably changed and enriched the urban living space. The project was also initially very controversial; an artist came from outside, had dealt with local and ecological conditions and had made a lasting contribution to enriching the public space of the city of Kassel. By documenta 8, Beuys planted 7,000 oak trees, each with a basalt stele. The impact of the work on the public is high today. Suddenly, the foreign was perceived as an enrichment of one’s own living space.

7.000 Oaks by Joseph Beuys, documenta 7, 1982

The trees with basalt steles are now part of Kassel’s cityscape.

I have my doubts that an artistic intervention like that of Joseph Beuys in 1982 will still be possible under the conditions of a Code of Conduct as proposed by the management consultancy Metrum. This further leads to excessive organizational structure.

Friedrichsplatz, documenta 14, 2017

The implementation of a Code of Conduct at the documenta is a forced voluntary commitment by curators and artists and definitely represents a threat to artistic freedom. The freedom of art and science is clearly defined and guaranteed in the German Constitution of 1949.