Prisoner of Love

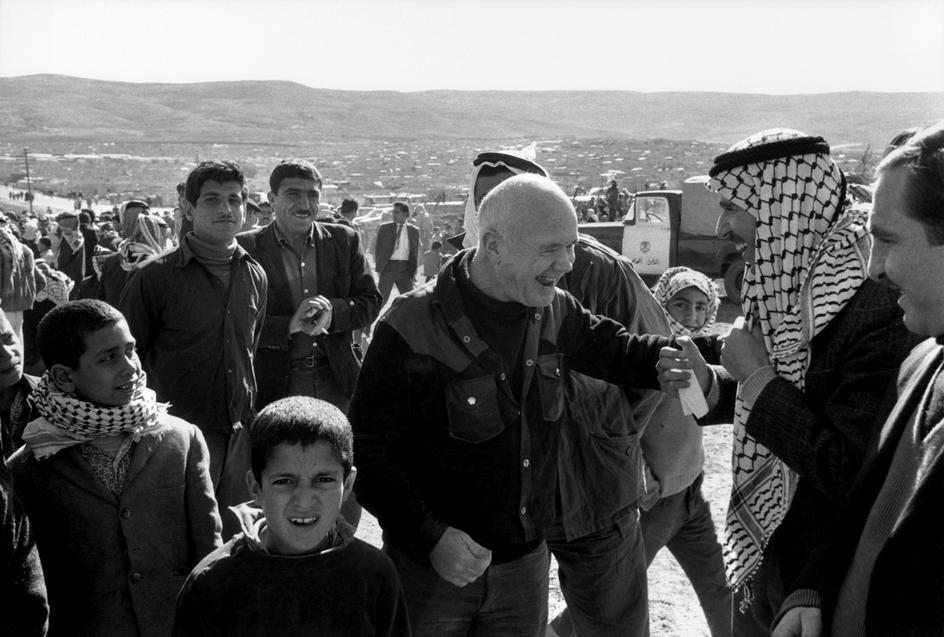

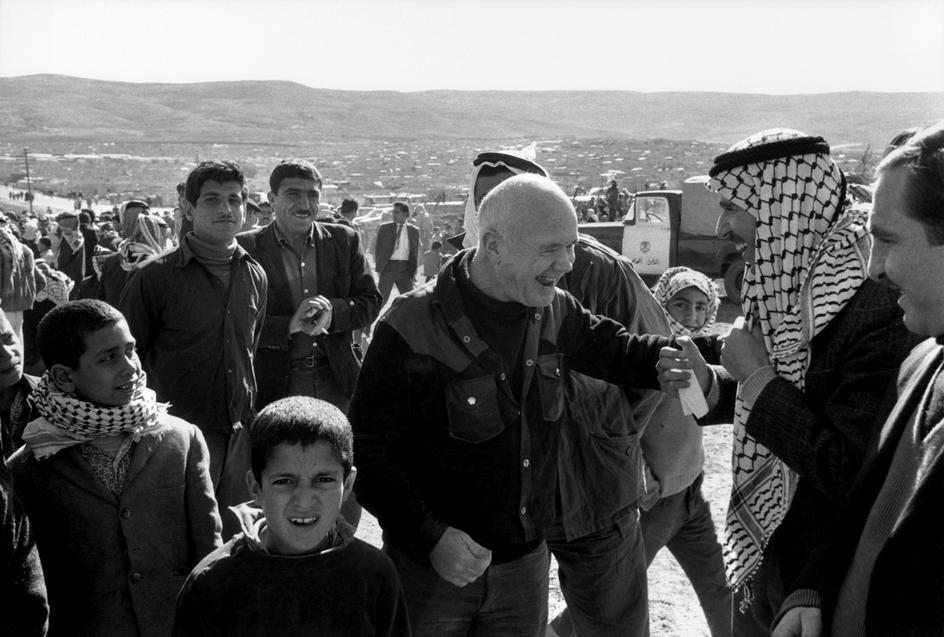

Starting in 1970, Jean Genet — petty thief, prostitute, modernist master — spent two years in the Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan. Always an outcast himself, Genet was drawn to this displaced people an attraction that was to prove as complicated for him as it was enduring. Prisoner of Love, written some ten years later, when many of the men Genet had known had been killed, and he himself was dying, is a beautifully observed description of that time and those men as well as a reaffirmation of the author’s commitment not only to the Palestinian revolution but to rebellion itself. Genet’s final masterpiece is a lyrical and philosophical voyage to the bloody intersection of oppression, terror and desire at the heart of the contemporary world.

Jean Genet was born on December 19, 1910 and died in 1986. He wrote poetry, plays, essays and novels. His most noted writings include The Blacks, Our Lady of the Flowers, The Thief’s Journal, and Querelle of Brest. During the early years of his life, Jean Genet was a criminal and vagrant.

September 16th, 17th and 18th 1982: During the Israeli operation: “Peace for Galilea” the Lebanese falangist militia, under Israeli army protection led by Ariel Sharon, massacre 2,750 Palestinian and Lebanese civilians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila outside Beirut. Jean Genet, a witness to the wreckage and slaughter has written a testimony, politically fierce and beautifully awesome under the title Four Hours in Chatila.

Excerpt from FOUR HOURS IN CHATILA by Jean Genet

“…. I must conclude my description of Chatila, which was briefly interrupted. Here are the bodies I saw last, on Sunday, about two o’clock in the afternoon, when the International Red Cross came in with its bulldozers. The stench of death was coming neither from a house nor a victim: my body, my being, seemed to emit it. In a narrow street, in the shadow of a wall, I thought I saw a black boxer sitting on the ground, laughing, surprised to have been knocked out. No one had had the heart to close his eyelids, his eyes as white as porcelain and bulging out, were looking at me. He seemed crestfallen, with his arm raised, leaning against this angle of the wall. He was a Palestinian who had been dead two or three days. If I mistook him at first for a black boxer it is because his head was enormous, swollen and black, like all the heads and all the bodies, whether in the sun or in the shadow of the houses. I walked near his feet. I picked up an upper dental plate in the dust and set it on what remained of the window ledge. The palm of his hand open towards the sky, his open mouth, the opening in his pants where the belt was missing: all hives where flies were feeding. I stepped over one corpse, then another. There in the dust, in the space between the two bodies, there was at last a very living object, intact in the carnage, a translucent pink object which could still be used: an artificial leg, apparently in plastic, and wearing a black shoe and a gray sock. As I looked closer, it became clear that it had been brutally wrenched off the amputated leg, because the straps that usually held it to the thigh were all broken. This artificial leg belonged to the second body, the one on which I had noticed only one leg with a foot wearing a black shoe and a gray sock. In the street perpendicular to the one where I left the three bodies, there was another. It was not completely blocking the way, but it was lying at the entrance of the street so that I had to walk by it and turn around to see the sight: seated on a chair, surrounded by fairly young and silent men and women, a woman – in Arab dress – was sobbing; she could have been sixteen or sixty. She was crying over her brother whose body almost blocked the way. I came closer to her. I looked more carefully. She had a scarf tied around her neck. She was crying, mourning the death of her brother next to her. Her face was pink, a baby pink, the same color all over, very soft, tender, but without eyelashes or eyebrows, and what I thought was pink was not the top layer of skin but an under layer edged in gray skin. Her whole face was burned. I don’t know by what, but I understood by whom. With the first bodies, I tried to count them. When I got to twelve or fifteen, surrounded by the smell, the sun, stumbling over each ruin, it was impossible; everything became confused. I have seen lots of crumbling buildings and gutted houses spilling out eiderdown and have not been moved, but when I looked at those in West Beirut and Chatila I saw fear. The dead generally become very familiar, even friendly to me, but when I saw those in the camps I perceived only the hatred and joy of those who had killed them. A barbaric party had taken place there: rage, drunkenness, dances, songs, curses, laments, moans, in honor of the voyeurs who were laughing on the top floor of Akka Hospital…..”