Topics

March 9, 2024All PostsThe exhibition of Isidore Fićović ”I am in a New Now”, lasted until September 8, 2023 in SULUV Gallery in Novi Sad. The exhibition is realized through the Exchange and Cooperation Program: Connect, Mark, SULUV 2023. It represents the process of rethinking the relationship between past – present – future , through the EYE of the present moment reflecting key sentences: “the spirit spreads like the light of thought” and “if you don’t say what you feel, you will stay without the heart.”

“I am in a New Now” questions what is that which makes a difference and stands between two worlds, between warm and cold, in the age of artificial intelligence and contemporary way of creating a new reality.

For Isidora,

Upon her exhibition in Novi Sad.

Is it a fight or a pact between machines and humanity? While we are dreaming about the future, does the future dream about us too? Are the macchines turning into us or we are the ones who are turning into robot?

I “feel” like I am in a simulation sometimes. When I wake up, it feels like a new stage of the game has started. I check my phone where I dive into another World. An artificial World where everyone is happy, rich, perfect and glamorous. The more we lose in real World ,the more we gain in cyber World. As long as we leave our pyshical World hungry, our persona is being fed. We turn off our feelings as soon as we turn our mobile phones off. When was the last time you really interact with the World outside? Listened to the birds’ chirping, watched a blue sky without recording it? What was the last time that you danced like noone is watching?

Once, I read about “Quantum Zeno Effect”, which describes the situation that an unstable particle, if observed continuously, will never decay. It can be interpreted as “ a system can not change while you are observing/watching it.” So, are we also can not change under the surveillance?

Today, machines can do many things from translation to content wrtiing. Even they can flirt with you. But, do they dream about you? How many gigahertz heartbeat is needed them to love you? Will your hearts be aligned in the same frequency while watching the sunset together?

And what about ethics?

Erkin Duman from Türkiye

Photo: Aleksandar Danguzov

exhibition is supported by Austrian cultural forum

www.isidoraficovic.net

@isidoravisualart

@isiartstudio

@suluv_gallery

@austrijskikulturniforum

Isidora Fićović / I am in a New Now

[...]

February 23, 2024Seen BeyondThe scandal that involved the 15th Documenta lifted a huge number of critiques and opened massive discussions about the freedom of art between artists and the public opinion.

What happened exactly? Just 4 days into the 100 – day show, the organizers declared that they would remove a piece of the exhibition because “triggers anti-Semitic readings”; the piece in question is called “People’s Justice” and was made in 2002 by the Indonesian Collective Taring Padi, portraying the difficult times that Indonesians had to face under the country’s military dictatorship. The artwork is not reserved for the country of Indonesia solely, but it’s more in general a denunciation of oppression that people have to face because of the world’s governments decisions, and it’s related to militarism and violence. The core idea of the artwork is, indeed, representing oppression in every form.

What caused the scandal was the presence of two particular characters presented in the art work: one of them was a man with side – locks and fangs wearing a hat emblazoned with a Nazi emblem, the other was a soldier with pig’s head, wearing a star of David and neckerchief and a helmet with “Mossad” written on it. It’s quite obvious the reason that caused the dispute: the artwork was considered offensive and carrier of old stereotypes about Jews; in response to the art piece, Israel’s embassy in Germany stated that Documenta was promoting a Goebbels – style propaganda and later, Germany’s culture minister Claudia Roth joined the critiques stating that to her, this is an anti-Semitic imagery. People’s Justice was removed, but this decision left a mark on the public opinion’s beliefs, polarizing the society between who believed that taking down the project was a good decision and those who thought this was an act of censorship.

Let’s take a step backwards first: this year’s exhibition was curated by the Indonesian art collective Ruangrupa and the idea of the exhibition was to set a different focus, instead of concentrating in the western hemisphere, the focus should be put on artists from the global south. By doing so, I think it’s important not to forget that other countries and other cultures have different sensitivities, and loaded topics in Germany might not be considered as much sensitive for other countries; furthermore, giving the internationality that Documenta has reached in the past decades, I believe that it is important to keep in mind that the exhibitions should be seen through different lenses and not through German eyes only. Back to the starting point, we said that the decision to take off the artwork from the exhibition polarized the public opinion, but the drop that broke the pot was the decision taken by Metrum to create a code of conduct to apply for the next exhibitions, to avoid other “incidents”. The decision was not accepted by many people, especially artists, whom are afraid that this measure will limit their ability to express their art completely.

The debate on what could and could not be exposed in a museum is a sensitive topic, and it’s up to the artist to understand when something could be considered offensive or not: probably the Indonesian collective should have thought that in a country like Germany, a clear exposition of Jewish characters would have been seen differently compared to them considering the country’s past. At the same time, if we stand with the censorship mind-set, the collective couldn’t have exposed publicly their perspective about the Israeli government and to me, this concept of hiding your thought from your artwork because it might not be liked by someone tends to be a wrong move. Personally, I believe that there should not be set any line or any restriction on art because it could be used as a powerful tool to initiate dialogue and create public debate, which is precisely what People’s Justice (which is the name given to the artwork) did; this is why I agree with the #standwithdocumenta initiative. The artwork from the Indonesian collective, as we said before, has the purpose of showing what oppressive governments do to people, and it’s not unknown that the Israeli government adopted a harsh behaviour towards Palestinians during the decades, so the critic is not towards the Jewish community or the religion itself, but against an oppressive government.

The problem here is obvious, where do we draw the line between freedom of expression and human dignity? When does art become too much? Article 1 of the German constitution states that “Human dignity shall be inviolable ” which means that freedom of expression finds its limits in denigrating someone’s personal dignity. On the other side, article 5 of the German constitution states that “art and sciences, research and teaching should be free. ” which, on the contrary, means that there should not be any restrictions on what artists make and teachers teach. These two articles seem to be contradictory, but the constitution also provides another important tool called Wehrhafte Demokratie (defensive democracy): this tool is used by the German courts to limit someone’s freedom of speech (or art) to save the main right provided by the constitution, which is human dignity (article 1).

Wehrhafte Demokratie demonstrates that closing up the artwork is actually a legal way to protect a community’s dignity and therefore, cannot be changed. However, this doesn’t mean that it cannot be criticized: as I said before, the artwork could have been a fantastic way of creating a discussion not only to reflect the Israeli government’s behaviour today, but also to reflect on the thin line that separates freedom of speech from the violation of human dignity but unfortunately, to me, the decision to take it down shows that institutions prefer putting on a patch instead of trying to initiate a deeper and more mature dialogue between people. [...]

February 8, 2024Events / TopicsWith the first and second documenta in 1955 and 1959, the initiator of the documenta Arnold Bode brought contemporary art from abroad, especially from the USA, back to Germany for the first time after the dictatorship of National Socialism. In doing so, he brought the other into your own. At the two exhibition venues – the Fridericianum and the Orangery in Karlsaue, which were still partly ruins at the time, the old and the new, our own and the others were mingled. The one became an enrichment of the other.

With this, the curator team around Arnold Bode and Werner Haftmann created an incomparable platform for an international dialogue beyond all borders, be it regional, national, ethical or gender-specific. The basis was created, among other things, by the German Constitution with its Paragraph on Freedom of Art and Science in what was then West Germany.

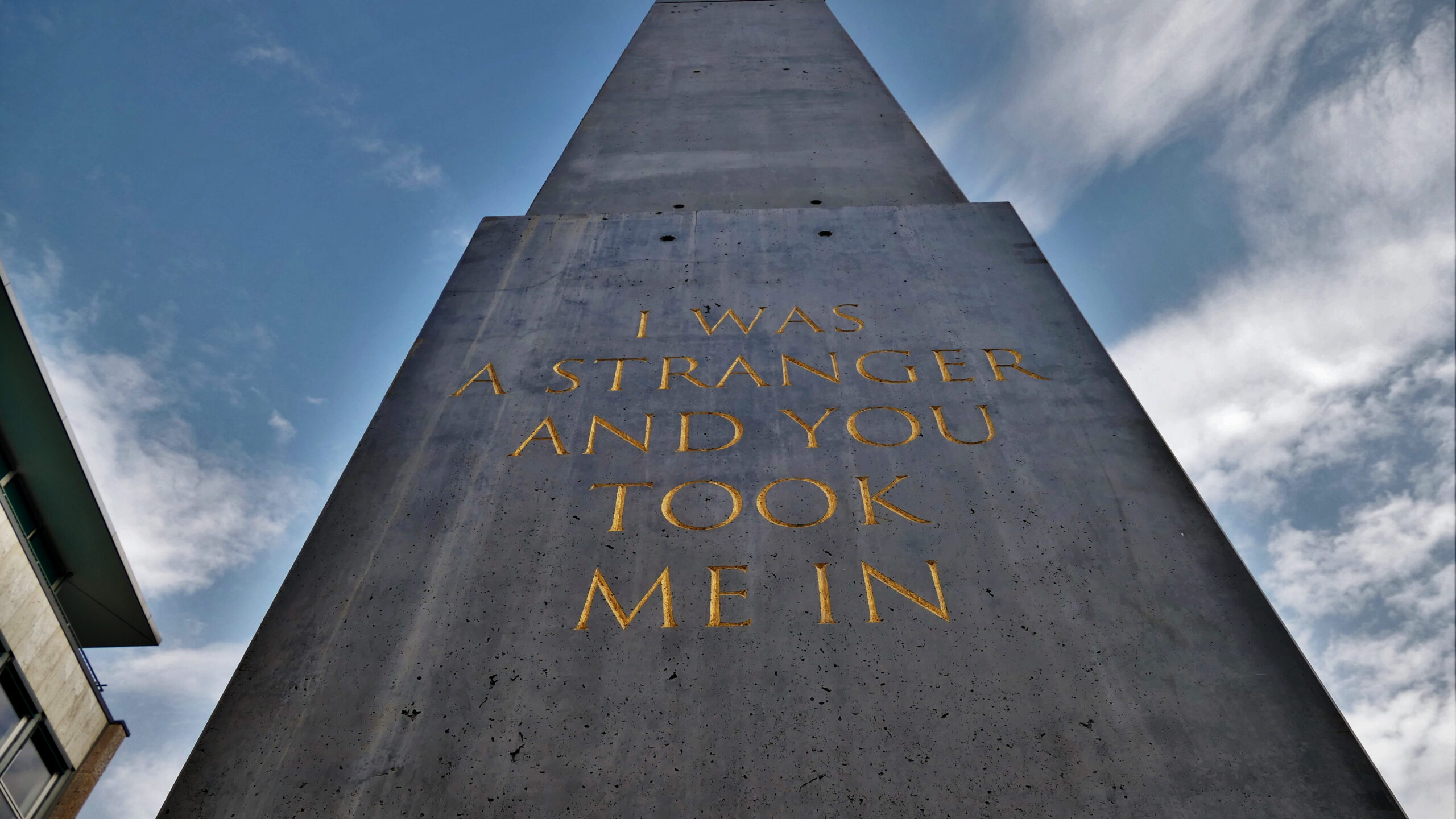

I was a Stranger, Obelisk at Koenigsplatz by Olu Oguibe, Documenta 14, 2017

A large international audience also travelled with the international artists. With 134,000 visitors, documenta 2 recorded even more interested parties than its predecessor. (The steady increase in visitors continued from then on).

This was always made possible under the responsible, creative leadership of the curator team with support from the administration, which made the organizational implementation possible.

Man Walking to the Sky by Jonathan Borofsky, documenta 9, 1992

Of course, there have always been controversies, but in dialogues they resulted in the artists and guests who were invited and arrived not being perceived as degenerates or threats, but rather as enriching their own culture and vice versa. So both were always experienced as enriching the other.

One of the many examples in this sense is the creative intervention by Joseph Beuys under the title 7000 Oaks – Urban Forestation instead of City Administration for documenta 7 1982 under the artistic direction of Rudi Fuchs.

This was an artistic and ecological intervention that sustainably changed and enriched the urban living space. The project was also initially very controversial; an artist came from outside, had dealt with local and ecological conditions and had made a lasting contribution to enriching the public space of the city of Kassel. By documenta 8, Beuys planted 7,000 oak trees, each with a basalt stele. The impact of the work on the public is high today. Suddenly, the foreign was perceived as an enrichment of one’s own living space.

7.000 Oaks by Joseph Beuys, documenta 7, 1982

The trees with basalt steles are now part of Kassel’s cityscape.

I have my doubts that an artistic intervention like that of Joseph Beuys in 1982 will still be possible under the conditions of a Code of Conduct as proposed by the management consultancy Metrum. This further leads to excessive organizational structure.

Friedrichsplatz, documenta 14, 2017

The implementation of a Code of Conduct at the documenta is a forced voluntary commitment by curators and artists and definitely represents a threat to artistic freedom. The freedom of art and science is clearly defined and guaranteed in the German Constitution of 1949.

Therefore, I ask you to join us to prevent this. [...]

January 4, 2024Drifting / Seen Beyond

“I am a musician, then I am a bit of a Black Sea person, but above all I am a revolutionary. And I don’t hesitate to put forward what I really know to be true, at least if I am forced to do so.”

“Ben bir müzisyenim, ondan sonra biraz Karadenizliyim, ama hepsinin ötesinde ben bir devrimciyim. Ve gerçekten doğru bildiğim bir şeyi en azından çok zorlanırsam ortaya koymaktan çekinmem”

During my time in Turkey I visited the province of Artvin on the Black Sea coast in the northeast of the country for the first time. Whilst I had the opportunity to experience the cultural, natural as well as the political settings that are given in the eastern Black Sea Region.

One of the biggest music icons of Artvin was Kazım Koyuncu, a Musician, Songwriter, Actor and Activist. With his lyrics, poems and speeches he was a left-wing pioneer and therefore a role model for many young people in the region.

He was born in November of 1971 in Hopa, Artvin. In the 80’s he moved to Istanbul to pursue his musical career and released his first songs with the Band ‘Zuğaşi Berepe’ (Children of the Sea). In the year of 2001 Koyuncu released his first solo album: “Viya!”

In the following year after his first big success, he was asked to compose the soundtrack for the popular TV series “Gülbeyaz” and also tried his hand at acting for a small role in the series. His breakthrough came with the ‘Hey Gidi Karadeniz’ concert series.

In 2004 after he published his second and last soloalbum: “Hayde” he fell ill with lung cancer which could later be traced back to the Chernobl disaster. In 2005 he gave his last concert and succumbed to the consequences of his cancer on June 25, 2005.

Kazım Koyuncu became the first musician with Laz descent to gain mainstream success and therefore contributed significantly positive to the identity of the Laz people. With his songs realized in Lazca, Hemşince (Homshetsma/Hamshetsma) Turkish, Megrelian and Georgian language he toured in the whole country.

In his music he added both authentic and modern elements to his music with bass, electric guitar, drums, and computer-aided sounds, as well as Black Sea authentic instruments such as Tulum, Kemen, and Kaval. Therewith he created a synthesis of traditional Black Sea Music and Rock Music and his unique style of music.

Since I only learned about the importance of Kazım Koyuncu due to Eda, a close friend of mine. I asked her what role he played in her life as a young woman being born and raised in Hopa.

Calling him “Brother Kazım”, Koyuncu always took a familial part in the lives of Eda and friends from the eastern Black Sea Region.

For her Kazım was not only any songwriter but was a political and philosophical idol. She was listening to his speeches at concerts, and still lives after his ideologies.

Her thought patterns on certain topics such as individualism, humanity, war, injustice, love, being a world citizen in his sense of living and more were consolidated and clearly shaped by the song lyrics.

Symbolic to the importance of him in her life, after his death Eda and her surrounding used to console themselves with the following sentence:

“Kazım abi ölmedi, aramizda yasiyor” (“Brother Kazım haven’t died, he lives with us”) [...]

October 23, 2023Topics

Franz Schubert lives in Vienna and Lower Austria. The artists works with digital media and 3D computer animation. His artistic practice reflects the visual frameworks of media environments and the ambiguities inherent in everyday perceptions and media structures.

During his three months stay in Summer 2023 as artist in residence of the Austrian BMKÖS (Ministry for Arts and Culture, Public administration and Sports) in Istanbul he drifted Istanbul in psychogeographical strolls in a correspondence with concepts developed by Situationist artist Guy Debord. Given that the layers of human habitation are thickest in cities, the project of psychogeography is to peel these away and reveal what is hidden, and what lies between the fissures of history.

Schuberts interest focused on the architectural structures made for Cats mainly in the districts Beyoğlu, and Şişli. Their diversity reflects the heterogenous structure of the Inner City around Taksim Square. The artist sketched the Cat Houses interpreting the different styles and forms of rapid urban growth in the metropol.

In his scetchbook the artists notes: “The city is home to numerous stray cats, many of which live in specially designed architecture exclusively for cats.”

In a serial of works Franz Schubert is experimenting with the concept of original and copy especially questioning the value of objects accumulated by its fame, pleading for a liberal handling of exchange of goods, knowledge and patterns. The copy of a Lois-Vuitton-Bag gets manufactered as a mass product in Turkey. Schubert rebuilt it during his residency to an exclusive Cat-residency.

With his practice, the artist became part of the cities pace by incorporating his concept into the architecture for Cats in Istanbul. He emphasizes that the caretaking of stray cats is a mechanism for creating a common sense absent in the political sphere. However, cat-residencies are portable, and they undergo a vivid exchange by people carrying them from one neighborhood to the other once in awhile. Some are anchored to the ground to withstand replacement. The artist left his Louis-Vuitton-Cat-House without any safeguards, free for exchange.

[...]

September 20, 2023Détournement / Events / Topics / Voices

The exhibition “Among Friends: One Chapter of a Long Story” showcases works by artist Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin (1957-2007) and 16 of his close friends. In her conceptual text, Curator Pelin Uran quotes French philosopher Jacques Derrida‘s reflection about the dilemma of friendship.

“There is a future, which is predictable, programmed, scheduled, foreseeable. But there is a future, l’avenir, which refers to someone who comes, whose arrival is totally unexpected. For me, that is the real future. That which is totally unpredictable. The Other who comes without my being able to anticipate their arrival.” ~ Jacques Derrida

During Alptekin‘s lifetime, his friends were closely involved in the artist’s constant search for innovation and new inputs. His passion for collecting items of daily use and his drift through Istanbul were usually done in company with others. “I am not a studio artist“, he would emphasize. His second nature was opposing common views and deconstructing the mainstream.

Alptekin was deeply influenced by Jacques Derrida, he had visited his lectures at the Sorbonne. Deconstructionism is rooted in what Derrida called Différance: meaning is not static but rather constantly changing, a constantly morphing competition between concepts. The continual inquiry keeps intellectually engaged in seeking alternative perspectives and comprehensions. There is no definitive conclusion; the process of inquiry is the ultimate goal.

The same intensity can be found in Alptekin life, as Pelin Uran points out: “ found his creativity and vital force in movement, in flights, in frontiers and in thresholds as something to cross, to go beyond. Otherness and displacement, the flow of immigration, not belonging, not feeling at home in anyplace, the desire to flee and the melancholia that accompanies it have been the major concerns both in his life and in his work, as well as threshold philosophical concepts like hospitality and hostility, creation and destruction, high and low”.

The exhibition evokes Derrida‘s conception of friendship, highlighting the fact that every friendship is structured from its inception by the possibility of one of the two friends passing away first, leaving the remaining friend to grieve. Alptekin’s unexpected passing in 2007 meant a huge loss to all those close to him. However, his spirit as an artist inspires his friends until now. “Among Friends: One Chapter of a Long Story” features some works of his wide friend circle.

“Among Friends: One Chapter of a Long Story” can be seen at Galerist in Istanbul, until 28.10.2023.

Participating Artists: Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, Can Altay, Thomas Büsch, Tunç Ali Çam, Grip-in (Ali Cindoruk, Eray Makal, Erhan Muratoğlu), Ayhan Hacıfazlıoğlu, Minna Henriksson & Staffan Jofjell, Şirin İskit, Emre Koyuncuoğlu, Michael Morris, Serkan Özkaya, Camila Rocha, Vahit Tuna and Nalan Yırtmaç. [...]

August 7, 2023All Posts / Places / Topography of MemoryFener Yoakimion Greek Girls’ High School was built during the Ottoman period in the Fener district. When schools for girls began to be opened in Constantinople in the 19th century, Patriarch II. Yoakim donated land for the construction of a school in Fener and the construction of the school started. The patriarch died before the construction of the school was completed, and Patriarch III Yoakim continued. The high school opened in 1882. Since both patriarchs contributed to the construction of the school, it was named “Yoakimion”, meaning “the work of the Yoakims”.

The school is located opposite the Fener Greek Boys’ High School.’ It was closed in 1988 due to a lack of students. In 2011, it was officially shut down. Unfortunately, the building, which is owned by the same foundation as the school, is currently closed to visitors. It was used for the exhibition of Greek artist Kalliopi Lemos, titled “Me, Between Worlds and Between Shadows”, as part of the Istanbul Biennial in 2013.

[...]

July 24, 2023All Posts / Events / Topics / VoicesAn illustration sheds light on the apathy of the international community towards the plight of Afghans, specifically Afghan women. Sharbat Gula, whose piercing portrait on the cover of National Geographic in 1985 put a face on war-torn Afghanistan, is now living in Rome, multiple outlets reported. The illustration shows a woman in a burka clutching a Sharbat Gulas photo, with the headline “Forgotten.” The Lady Liberty Library contains several witty works by Afghan female artists, which fight distorting imagery.

Parwana Haydar’s video collage, titled “Foot ache,” is displayed on a video screen located in the Hallway of the courtyard. The video was created using artificial intelligence and shows a young Afghan girl dancing on a rubble-covered surface to the traditional frame drum ‘daira.’ The Artist is a member of the AVAH Collective, a group that researches and shares multimedia about Afghanistan. It arose due to a lack of available information and long-term initiatives regarding the historical and contemporary practices originating in or related to Afghanistan.

The Goethe Institut Kabul, a cultural institution of the German Foreign ministry, had to move to Berlin in 2017 after a terrorist attack. A “Focus Afghanistan” event was held at the “Goethe Institut in exile” in Berlin and showcased artists and social activists.

ArtLords is a group of artists and activists from Afghanistan who want peace and progress instead of war and warlords. Collectively created murals are produced in public space. InEnArt talked to the Founders in Berlin at the end of June. Omaid Sharifi is commuting between the US and Afghanistan as a voice for greater civic rights. Kabir Mokamel has relocated to Kabul from Istanbul and emphasized that “my work makes sense in Kabul.”

ArtLords and others try to prevail over Warlords

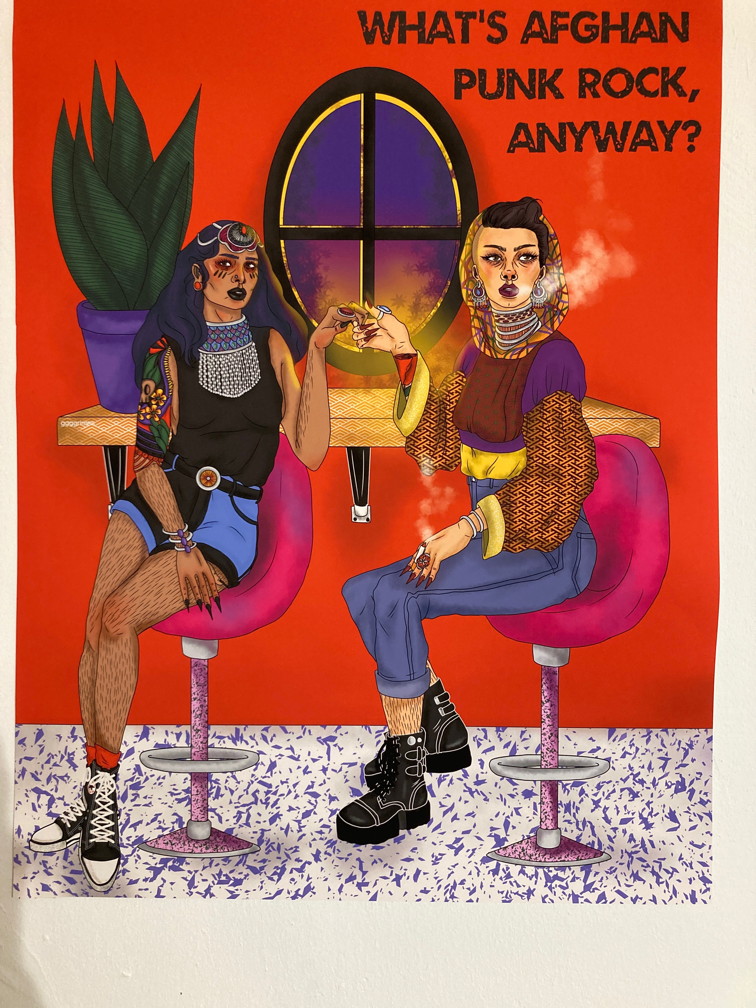

Some of the pictures in the video are from Afghan Punk, a Berlin-based multilingual community magazine that connects liberation struggles with creative storytelling. Armeghan Taheri started it up, and it’s a hit with the younger Afghans living abroad.

On August 15, 2021, the Taliban seized Kabul and overthrew the Afghan regime. Most Afghans think of the day as point zero. About 1.8 million Afghans left the country, making the total number of Afghans in neighboring countries 8.2 million. This is one of the most serious refugee situations in the world.

Rising poverty, restrictive policies, unfair treatment, and the marginalization of women from public life are triggering intense conflict. Women are not allowed to go to schools or universities, suicides and murders are increasing, and activists talk about femicides.

[...]

March 6, 2023Events / Seen Beyond / Topics / VoicesNawar Bulbul is an actor and theater director living in Aix-en-Provence (France). He was born in 1973 in Homs, Syria. Nawar’s father was a communist creating theater performances for the working people. His mother, a deep believer and religious person (1). Nawar’s vision was strongly influenced by his father’s work, and was one of the reasons why he decided to commit himself to the theater. A passion that brought him to enter the Dramatic Arts Institute of Damascus, where he graduated in 1998.

Lately, touched by the authoritarian government of Bashar Al-Assad and the political instability of the country, Nawar started to engage in the anti-regime demonstrations that were taking place in 2011. His critical vision and desire for freedom were too dangerous for staying in Syria. For this reason, he decided to quit his country to throw off his chains and develop his artistic career without threat.

Nawar Bulbul in his play Égalité (202 1)

“My limit is the sky”

“There is some kind of nostalgia”, Nawar says. When he remembers his years in Syria and reflects about his current situation in France, Nawar affirms that he can’t forget his friends and family there. He points out that he graduated there, and had lots of memories which he had to leave. “Suddenly, you have to leave everything. Every memory there”.

However, Nawar considers himself a French man now. “I’m free”, he says, and he notes that in France, he can do what he wants with his work. “Here, my limit is the sky. Nobody can say what we can’t do”, he states. But Nawar also mentions the censorship that still remains inside his head: something abstract that stops him from being completely free. He describes it as something like police, religion and dictatorship. Something implanted in his head which he tries to kill. “This is my battle”, he states.

Nawar says that theater is like medicine. He feels so passionate about it and doesn’t feel like working. “When I’m doing theater, I feel in vacation”. Of course, he needs to make a living and bring money for his family. But he affirms that it doesn’t feel like a job for him. He is so happy on the stage and everywhere in the theater, that he doesn’t get tired. “This is my motivation, my happiness. This is my life”.

Nawar Bulbul developing Shakespeare in Zaatari (2014) with Syrian refugees

Nawar Bulbul has a big CV: he has worked as an actor and director in several films, tv shows and theater plays since 1998, where he debuted as a professional with the Dramatic Art Institute of Damascus. His work has also been published in several journals and recognised media, such as Arte, The Guardian, Le Monde and even The New York Times.

The most recent theater plays of the Syrian director that have received press coverage are Shakespeare in Zaatari (2014), a play with children set in the Syrian refugee camp “Zaatari”; Romeo and Juliet: between siege and refuge (2015), a work done with children separated by war (from Jordan and Syria) which were reunited via Skype for their final performance; and Love Boat (2016) a tragicomedy with adult Syrian refugees touched by war and living in Jordan.

Nawar Bulbul’s Love Boat (2016)

Nawar affirms that “the three biggest taboos in the Arab society are: religion, sex and politics”. He has been trying to fight against these taboos through his works, and that’s one of the reasons why he feels good in France. “In Europe, when they separated the Church form the State, they started to see the future”. Nawar talks about the corruption and the control of Arab governments, and affirms that they are doing this to control the people.

The great thing about theater, Nawar says, is its authenticity. The fact that you can do, modify and perform whatever you want. “You’re with me and I’m with you. This is the life”. The difference with other media and arts is that you don’t have to follow a paper and repeat it. “Can I change? No, no, no. This is my text. This is my Bible”, a cinema or tv director would say. In the theater, instead, you have plenty of “shining moments”.

“The culture is food for humanity”

After more than 25 years dedicating his life to theater, Nawar Bulbul stays motivated, passionate and optimistic. If he had to go back in time and choose a profession, he would select theater again. “Of course, one more time. And second, and third, and fourth time”. Even if he is working alone most of the time, he receives the visits of some French friends that come to his house to watch his rehearsals, give advice and ideas.

For Nawar, theater is something that feeds your soul. “The culture is food for humanity”. And he states that he’s doing theater not only for Syrians, but for all the people. At the end of the interview, I asked him about his biggest dream. “My hope is to be able to come back to Syria”, that the government of Bashar Al-Assad finally falls, and he can find the peace in his country.

Vulin, V. (2016). Nawar Bulbul : un artiste syrien sur les sentiers de la liberté. Cairn.Info. Available at: https://www.cairn.info/revue-confluences-mediterranee-2016-4-page-123.htm [...]

February 16, 2023Place Hacking / Places / Seen Beyond / Topics / Voices

Raphael Vella is an artist, curator and teacher based in Malta. He did a Bachelor’s in Education (1991) and a Master’s in Arts (1997) at the University of Malta and concluded a PhD in Fine Arts at the University of London in 2006. Since 2009, Vella has been curating exhibitions and creating diverse cultural initiatives such as the Valletta International Visual Arts festival (VIVA). From 2000, he has enjoyed several artist residencies around the world, and his artworks have been exhibited in many international contexts. Currently, he is also an Associate Professor at the University of Malta and has worked extensively to promote the work of emerging Maltese artists (1).

Raphael Vella participated in the Mahalla Festival – Murmuration– 2021 in Istanbul with the installation and the stop motion animation Antibody. His new work News from Nowhere was on display in Japan 2022 and will be on display in Malta at Valletta Contemporary this year, curated by Maren Richter.

INTERVIEW with Raphael Vella

By Maëla Sanmartín

Did you always want to be an artist?

I think so. When I was a kid, both of my parents were teachers, so there were lots of books at home. Neither of them was an artist or had any kind of inclination towards art, so it didn’t really come from them. But I remember the house was full of books and paper. And I would make lots of drawings on these, any piece of paper I found around the house. In the beginning they thought I was just scribbling. But then they realized it was more than that, because it was an obsession. They started sending me to lessons, and that’s how it started.

Would you say that art is political?

I think it’s important that art has to be political. In my case, I’ve always been interested in the relationship between art and politics. Also, the more I matured, the more I understood how important it is to think about the relationship between art and life. I never liked the idea that art is simply a case of letting your imagination run loose. Of course, I like creative ideas in art, and I tell my students it’s really important to be creative. But I’ve always thought as well that it’s important to ground that creativity in real life and social issues.

You’ve worked with diverse topics like migrations, gender, medicine, history… Which one would you say is the topic that touches you the most?

I’m interested very much in the relationship between medical, political and educational practices. In a sense, all those different disciplines try to improve our lives. And my question is: can we actually do anything to generate a change? And do artists need to be given this kind of extra responsibility? Are artists like teachers, or are they expected to be like doctors? If you go to a doctor because you’re sick, you expect to get better. Do you go to an artist for the same reason? This is a question I like to ask myself all the time, and it’s at the bottom of what makes me move forward as an artist. Thinking about the relationship between art and healing.

Raphael Vella. Medical School, 2012.

You have a quote on your website: “no matter how much we attempt to destroy or forget our past, it returns to haunt us”. What relationship do you have with the past? How does it influence your art?

All art or literature is a kind of reaction to what has already come before us. So you can’t really ignore the past or erase it. In my work, I have sometimes tried to use processes of erasure. For example, using pages from books and crossing them out. When doing this, the text is still there, it’s still visible. Even if it’s not as legible as it was before. And this is a way to show that no matter how much you try to forget your past, your past is still going to haunt you and it’s still going to be there, all the time.

What are your sources of inspiration?

Current events sometimes inspire me. But also the future, the unknown. And the fact that the future is a bit shaky, a bit scary, because you’re never sure what’s going to happen. Now, with so many issues related to climate change and so on, the future doesn’t look great for future generations. And that is something which I think about quite often. I also usually think about any situation in which we communicate with others, what I call dialogic situations. Situations which make me create some kind of dialogue with other people, or assemblies of people coming together to try in some way to improve their lives.

Raphael Vella. Antibody, Installation and Stop Motion Animation in Istanbul 2021

Do you believe in something like a revolution, with art involved?

The easy answer to that question is no. Nobody’s going to expect art to create some kind of political revolution that will change the world, in the same way that the French Revolution changed Europe, for example. So, the answer is no. But I do believe that art and other aspects of art, for example in educational settings (not only with children, but also with adults) can be part of a slower process. However, very often it’s so invisible. But just because you can’t see it, it doesn’t mean it’s not there.

Which one do you prefer: teaching or doing art?

That’s a difficult question. Well, I think in my heart I prefer art. You know, I’ve been teaching for over 30 years, and I think I’ve given students enough. Don’t get me wrong, I love teaching, but it’s something you must do in a way for a living. If I would have tried to survive only through my art, I would have probably died of hunger ages ago (he laughs).

What do you think is the power of teaching and the power of art?

The power of art is, I think, the power of empathy. Connecting with people you don’t even know. The power of teaching is the ability to connect with people you do know. And this is a beautiful process which grows over time.

Does art have a meaning for you?

Yes. I mean, for me that question is the same thing as if you were asking me “does life have a meaning for you“?

Raphael Vella. News from Nowhere, Stop Motion Animation 2022

Is your future predictable or unpredictable?

I don’t know if I’m going to be alive in three years, so I don’t plan it too much, you know? But to some extent, I’m kind of in control of my future. I tend to plan projects one or two years ahead. But not much longer than that, because then it becomes too far in the future. And then, in your daily life I get these moments of unpredictability. For example, getting invitations, being part of exhibitions or projects. So I never know, perhaps next week I will get an invitation to be part of a project, and it happens. So yeah, to some extent I can say my future is predictable. Luckily, it’s also unpredictable, because even when you’re doing your own art, you’re never a hundred percent sure what’s going to happen.

We did an interview with Aaron Bezzina on InEnArt, who is also an artist living in Malta. I wonder if you, artists in Malta, are in contact or create cooperation networks.

Aaron was my student, for like a year or so. And I know him from other things, because I curated two or three exhibitions in which he was involved. At that time, he was an emerging artist. Now he’s more established. But your question is perhaps more important than you can imagine, because here in Malta (despite our small size) there is not much collaboration, unfortunately. Around 18/19 years ago, I coordinated a group of contemporary artists. There were around 10 of us, but it lasted perhaps three years, not more. It was difficult to survive for longer. So it’s not easy to collaborate, but I don’t feel guilty about not having offered a hand.

What can you tell us about your latest work, News from Nowhere?

It’s called News from Nowhere because it was inspired by a novel written by the socialist William Morris in 1890. He really had this kind of utopian belief that art can change society, and he believed it could change society through work. If all work could become like a form of art, then you would enjoy going to work. He was very much inspired by Marx’s ideas, and he wrote this novel where the main character basically wakes up in the morning and finds himself in a completely unknown world in the future. And this world has been transformed into a kind of communist paradise where everyone loves going to work and he’s walking around the streets. But he totally doesn’t recognize the place or the people, because everyone seems happy.

So what I did in my animation is that I took the basic structure of the novel, but then turned it completely upside down. It’s only a five-minute animation (but it has about a thousand frames) where you get someone waking up, going out and finding a completely transformed world. But it’s a world on fire. The whole place is literally on fire, and there are explosions everywhere. Later, the man just returns home completely shocked. He looks at a plant, waters it and that’s the end of the animation. So, even if the world around us is changing (maybe for the worse) there is still hope and the possibility of dreaming of change.

Raphael Vella (n.d.). raphaelvella.com. Available at: http://raphaelvella.com/ [...]

February 16, 2023All Posts / Events / Place Hacking / TopicsThomas Geiger studied Fine Arts in Karlsruhe and Interdisciplinary Art in Tallinn, Estonia and is now settled in Vienna as a performance, sculpture and language artist with a focus on public space.

He is currently in Istanbul for a 3-month stay as part of the International Residency Program of the Austrian Cultural Ministry accompanied by the Austrian Cultural Forum Istanbul and Diyalog.

Co-financed by the Goethe-Institut, he was invited to the “Arter” Museum, one of the most renowned art houses in Istanbul, to present his performance “The Pigeon“, adapted to Turkish public space.

However, under the current conditions, triggered by the terrible earthquake in southern Turkey, Kurdistan and northern Syria, the performance has been cancelled until further notice.

Geiger plans to realise the performance in another house or place in a respectful way towards the earthquake.

In his performance “Le Pigeon” (The Pigeon), first realised in Paris, Thomas Geiger shifts the perspective of the recipient and focuses on the omnipresent pigeon in public space. In doing so, he gives a voice to the expert for this space, as Geiger calls the pigeon, in order to draw attention to its living space, which is threatened by privatisation.

In the continuing version in Istanbul the pigeon is to remain the protagonist as a recurring character, sharply criticising and questioning the advancing privatisation, which is often only distinguished from private space by only fences or walls.

In this way, he places objects of everyday life and daily perception in a slightly shifted context and encourages the recipient to rethink the prevailing structures.

In his new project “Istanbul Simit Exchange”, Thomas Geiger plans to buy a vendor’s daily supply of simits and offer them to pedestrians for free. In return, he invites them to draw their own simit on a sheet of paper as a value compensation. As is well known, the steadily decreasing purchasing power of the Turkish lira can be illustrated by the price of simits and underlines the ever-shrinking, affluent middle class and ever-increasing poverty in Turkey. The basic idea of the project is to take up and critically question the issue of value representation and the payment for creative work. So you don’t pay for your simit with money, but with a small, creative, self-produced piece of work. These creative imitations of the simits will then be sold in Vienna as components of his project “I want to become a millionaire”, which has been running since 2010.

The performance was canceled because of the earthquake that took place Feb 6 in Turkey and Syria. Instead the artist will prepare a video of the performance which will be screened later on. Watch out for further notification. [...]

February 12, 2023All Posts / Events / Seen Beyond / Topics

“The return of Rosinante” (Rosinante’nin dönüşü) Şerif Kino titled his latest show. One of the strongest works shows the fall of the knight and his horse into a reddish, fantastic landscape, which appears clouded by animal figures. Disproportionate and shadowy, a bull and the hindquarters of a zebra peer out of the mist. A parrot and fish appear to be heading west, a rooster is bisected by the end of the canvas. The mishaps of horse and rider are completely ignored by the mythical animal figures. Their failure is either irrelevant or ubiquitous, like the ongoing destruction of nature by an Anthropocene turning itself into a black hole.

“I had bad timing,” stressed Şerif Kino during the opening of the exhibition on February 10. Due to the earthquake disaster that hit south-east Turkey and north Syria, it had already been postponed by a few days. Kiziltepe, where Kino lives, wasn’t too badly affected, but it is surrounded by the disaster area.

When I walk through the exhibition, I have a different opinion. Actually, the themes correspond perfectly with the present. A natural disaster occurs as the zero point of existence. While the trappings bobble in old dilemmas. Efforts and good intentions are corrupted by greed and corruption. Collapsing new buildings bury thousands of people under their own belongings, which are exposed in the cracking concrete.

Before setting out on his adventures, Don Quixote decides that as a knight-errant, he must choose and name a horse. He deliberates about the name for four days before settling on Rosinante for the old and rather sickly horse. Don Quixote picks a name that means “ranked before all other horses,” which shows Don Quixote believes this horse to be capable of great adventures.As much as Şerif Kino does.

Since 30 years the Şerif Kino analysis the metaphorical universe of the literature classic. His tenacity is almost like that of the hero he has chosen as his lifelong inspiration. He used sculpuring but mostly painting in different styles, mixing concrete and abstraction in an anachronism.In particular, his images in this exhibition move from figuration to dreamlike transitions of color and form, blurring into a very contemporary abstraction from reality to internalize the recurring theme of loss and failure of the image of the still never-giving-up hero.

The main figures are rarely looking alike. They often are contextualizable by the eye of the viewer. The motive of master and servant, horse and donkey are universal, the earthy tones transferable. I could also see parts of the scene of the unfortunate young people, who went to Iraq from the village of Roboski in 2011 to be shot by the Turkish military as supposed PKK military units. But thasts up to my interpretation.

Born in 1967 in Kiziltepe, Mardin, Şerif Kino started his art-Carreer in Istanbul after graduating from the Art Faculty at Marmara University. He attended as a young artist to a group show in the Press museum in Çemberlitaş. The second exhibition was opened in the Marmara Museum at Taksim sqare. I beleive to remember the clay figure of Don Qixote in the Marmara Hotel. But maybe I am mistaken. That was in 1994, two years after I had moved to Turkey to work for German television in the war-torn 90’s. If I had known then that the artist was from Mardin, it would have been very important to me. We were sent to Diyarbakır and Mardin, the cities were under emergency law. Turkish military was fighting PKK units. Locals “disappeared,” Hezbollah, a Kurdish Islamist movement, murdered people they saw as connected to the Kurdish political movement. Admired figures like the writer Musa Anter were assasinated. Counter-Terrorism was a strategy of the Deep State.

Don Quixot as a motive was very meaningful then and kept being for Şerif Kino. He moved back to Kızıltepe years ago when the Emergency Law was lifted under the rule of the Islamic Conservative movement. A peace process started and failed. The country is still longing for heroes that are ultimately sentenced to failure somehow. Not only in Turkey but globally it seems to me. As these lines are what I see in the return of the motives of these works.

“The Return of Rosinante” is the 21st solo exhibition of the painter Şerif Kino in his 30-year art career.

ZibaArt Gallery, 10. – 28.02.2023. Curated by Fehim Güler and Şerif Yaşar. [...]