8 March Working Women’s Day

“I couldn’t stand the injustice any more,” explained Ayten Kargın, a 57-year-old woman, referring to the conditions she faced working as a cleaner for a family living in an Istanbul gated community close to the Bosporus.

Kargın began the job to help pay for the eldest of her three children to go through university and make up her husband’s wages as a slaughterhouse butcher.

Born in the poor eastern province of Tunceli, Kargın left education after primary school and married at 18. Moving to the metropolis of Istanbul, housework was the only occupation she knew.

She worked for the family five days a week from eight in the morning, until six at night, ironing, cooking, cleaning windows, taking the dog for a walk and sweeping carpets. “I wasn’t aware in the first years that I was part of professional working life,” she said.

When in 2014, after 13 years, her employers said they wanted to replace her with a younger worker, Kargın went to the IMECE domestic workers’ union for advice. The family responded by sacking her without notice.

With the support of the union, Kargın became the first domestic worker in Turkey to bring a court case against her employers for working uninsured. “I had so many accidents at the working place, I never asked for anything,” she said.

Having no written contract, to prove she had worked for the family, Kargın managed to obtain records from the gated community entrance to prove her coming and going and convinced a housekeeper to be a witness for her.

Kargın’s courage and endurance led to the court ordering her employers to pay her social security contributions for the years she worked, assuring her a modest retirement pension. She was also elected to the board of the union.

Kargın’s case is a milestone for labour rights in Turkey, but is nevertheless rather exceptional.

Just 28 percent of Turkish women aged 15 or over have a job, according to the state-run statistics institute, compared to 65 percent of men. Women’s employment surpasses men’s in the farming and the services industry, where 55 percent of women with a job work. Nineteen percent of all Turkish women with a job work part-time versus 6.5 percent of men.

Informal employment in domestic service is one of the leading sectors in which unskilled women work, especially in urban areas.

“The complexity of the employment relationship, exclusion from social protection, the lack of a stable job description and the special character of the working space, make occupational health and safety measures actually more important for domestic workers,” said a 2013 report by the University of Pamukkale in western Turkey.

The IMECE union is currently helping the family of Rukiye Şimşek, a 42-year-old mother of two who lost her life falling from the third floor window she was cleaning. Her family is suing her employers for negligent homicide, but since there are no labour regulations governing domestic work, the outcome is far from certain.

There are no official numbers of domestic workers in Turkey, nor figures for how many have died or been injured at work, but it is one of the biggest sectors of informal employment in the country.

A report published by Gülay Toksöz for the International Labor Organization in 2013 estimated 121,000 people were employed in private homes, about 90 percent of them are women. Experts say a rising number of foreign, illegal female workers in Turkey are facing exploitation, physical and sexual violence.

According to the DİSK and Genel İş unions, only three out of every 10 women are employed, half of them unregistered outside the social security system. Every fourth woman is facing violence every day, the number of under age marriages is increasing and at least three out of every 10 females married in 2017 were under the age of 18.

Mine Eder, professor of political science and international relations at Istanbul’s Bosporus University, said these developments were a result of complex shifts in Turkish society. Beside structural aspects, like the decline of the agriculture workforce, where women used to be more active, gender roles are governed by a conservative male dominance. One dramatic result is the rise of violence against women. “We are not even able to discuss gender inequality in the working field in an environment where we are witnessing women’s murders every day.”

Not only women in the low-wages-sector duffer inequalities. Artist Gonca Sezer was a teacher for art education at private schools in Turkey for 25 years. “It is a less important branch according to the general opinion. You get the lowest wages as a teacher that’s the only reason for the dominance of women as staff. Very often you are supposed to be the maid-of-all-work for designing the decoration at school celebrations, tinkering garlands and arranging Balloons. As an artist I experienced myself and witnessed a lot of inequality in the recognition and evaluation of works produced by men and women.”

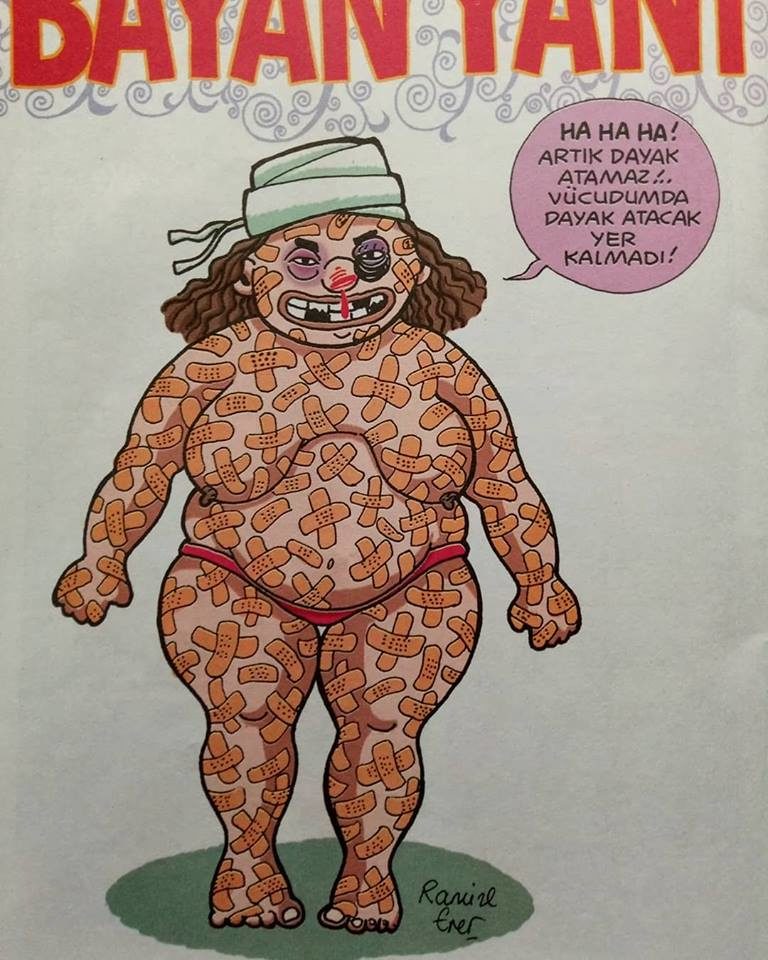

At the satirical magazine “Bayan Yanı”, all the cartoonists are women. Its March edition highlights the issues women face in Turkey in a tragicomic way. Betül Yilmaz ridicules the tendency to hide domestic violence among urban women professionals. “Make-up-Video-Mind” is a strip about a female video blogger teaching her audience how to cover up marks of beating. A drawing by Ramize Erer shows a woman with swollen eyes, her body covered with plaster, her head bandaged, saying, “Haha, there is no place left, where he can beat me!”

Cartoonist Ipek Özsüslü produces strips about child marriage. “My mind is flipping drawing pregnant schoolgirls,” she said with an expression of disgust. “But this is part of our reality.”

Özsüslü said she would be demonstrating as part of a march in Istanbul to commemorate women’s day. “We will be out on the streets … we won’t miss the opportunity,” she said with relish. They were also busy at the domestic workers’ union, painting placards for the event.

“No to heaven for the rich and hell for domestic workers,” read one.