Sense of Adventure

What happened to playgrounds that give children space

A summer festival in London gives kids the chance to run wild on two temporary playgrounds that will fire their imaginations

at The Guardian

Van Eyck springs to mind because of the London Festival of Architecture, which is tapping into Olympic fever this summer with the theme “The Playful City”. As part of the programme, two temporary playgrounds are opening in King’s Cross next weekend. One is a series of installations made of recycled materials by students from Central Saint Martins, and the other is the Imagination Playground, a kit of parts designed by the Rockwell Group, which children can assemble like a giant puzzle. No doubt these will be enjoyable additions to the developer’s playground that is currently King’s Cross. To me, however, there is no playground like an adventure playground.

Van Eyck springs to mind because of the London Festival of Architecture, which is tapping into Olympic fever this summer with the theme “The Playful City”. As part of the programme, two temporary playgrounds are opening in King’s Cross next weekend. One is a series of installations made of recycled materials by students from Central Saint Martins, and the other is the Imagination Playground, a kit of parts designed by the Rockwell Group, which children can assemble like a giant puzzle. No doubt these will be enjoyable additions to the developer’s playground that is currently King’s Cross. To me, however, there is no playground like an adventure playground.

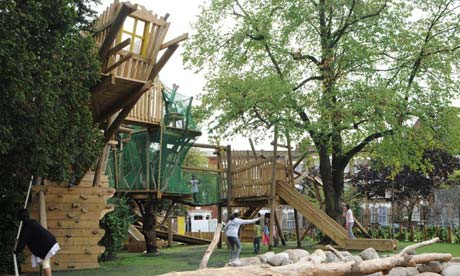

I remember the summer of 1984 not chiefly for the Los Angeles Olympics, but for the discovery of my local adventure playground. Whatever Carl Lewis was up to, my younger brother and I had imaginary pirate ships to board, with real ropes and wooden platforms – and the rope burns and splinters to prove it. There was even a zip cord, which put us in true Indiana Jones territory. Here, in this visibly anarchic place made of old telegraph poles and wonky planks, was an urban anomaly that tolerated mess and wild behaviour. This was brilliant, because it’s hard to emulate your heroes on a mere seesaw.

Van Eyck believed playgrounds should challenge a child’s imagination without jarring the adult’s aesthetic sensibilities. His abstract, elementary forms – often manufactured out of metal tubes like modernist furniture – were meant to belong in a well-mannered streetscape. During the same period in Britain, however, we were developing a tradition of playground design that was almost diametrically opposed. The first “junk” playgrounds emerged amid the rubble of the Blitz, and the results were far less polite. Consisting of makeshift structures cobbled together out of roof beams and detritus, they were often designed with the assistance of the children themselves. That essential character survives today in descendants such as Glamis Adventure Playground in Shadwell, east London, a riot of skew-whiff woodwork and clashing colours, and an odd hybrid of post-war austerity and postmodern assemblage.

read more at The Guardian